I’ve been sports-pilled. I’m not sure when it started, but I can tell you when I knew: The Olympics were winding down, I was watching rhythmic gymnastics, and it struck me with a pang that in a matter of days there would be no more of this, this pageant of human effort and excellence. No more synchronized diving. No more twirling shot-putters or pole-vaulters flying backward through the air. Farewell to the impassive, agile grapplers, and to the whiplash pleasure of a badminton rally. Or—wait—I interrupted myself. Tennis! Tennis has rallies! How many days until the US Open? Could I make it until then?

I guess everyone’s been sports-pilled. Because, wow, the Open was a scene—Taylor Swift, Kendall Jenner, movie stars, and influencers everywhere. Maybe they’d all gotten really into Challengers. Or maybe this was part and parcel of a turn in the zeitgeist, which is what I suspect. Because around the same time, the spring 2025 fashion season was underway, and it was like you couldn’t throw a stone without hitting a sports star. Gymnasts, sprinters, basketball players, footballers, boxers perching their muscular butts on seats at Michael Kors, Tommy Hilfiger, Carolina Herrera, Burberry, Bottega Veneta. And more. I even spotted dapper fencer Miles Chamley-Watson at Fendi. So this isn’t just about tennis. But—returning for a moment to the US Open—consider the destiny of the two men who played the final. Not long after concluding their showdown at Arthur Ashe, both flew to Milan, where Jannik Sinner sat front row at Gucci, and Taylor Fritz walked the runway at Boss. Meanwhile, up in the stands, Taylor Swift was watching that Fritz-Sinner match with her NFL-star boyfriend Travis Kelce and his Kansas City Chiefs teammate Patrick Mahomes, who’d turned up camera-ready in, respectively, Gucci and Prada.

“If I’m in the city during Fashion Week, I’m not not going,” declares top-ranked player Frances Tiafoe, who, straight after dazzling Open-goers, made a beeline for IB Kamara’s Off-White show. It was held on a basketball court. Women’s US Open champ Aryna Sabalenka and Olympic gymnast Suni Lee were there too.

I reel off this very non-comprehensive list of recent sports-fashion mash-ups because, bluntly, as trends go, it’s weird. Since time immemorial, there has been Sport, and there has been Fashion. At an apparel level, the two do habitually converse—Coco Chanel launched her business making tennis dresses, and today’s athleisure has antecedents in Claire McCardell’s bodysuits and Y2K-era Prada Sport. They call it “sportswear” for a reason. And it is likewise true that there have always been individual athletes with loads of style. But as cultures, as worlds, the runway and the stadium kept their distance, with rare exceptions (David Beckham, the Williams sisters) proving the rule. Now the stadium is the runway: The “tunnel ’fit,” the pregame looks athletes wear ambling from team bus to locker room, has turned NFL and NBA players into tastemakers, with stylists pulling items straight from Paris shows and millions following fan accounts like @leaguefits.

“I have a team of stylists—there are three of them that work together,” explains Boston Celtics forward Jayson Tatum. “My biggest nonnegotiable is, I’m six feet nine, I’ve got a 32-inch waist, and I want to be comfortable—I spent enough time, especially when I was younger, wearing clothes that didn’t fit. So now we have a tailor in New York and a tailor in LA, and when my stylists find a pair of pants, they go straight to a tailor who has my measurements.” Other pieces are custom-made. His wardrobe, he says, has basically taken over his house. In the locker room, he and his teammates chat about their tunnel looks. “We notice, we compliment each other…. If somebody looks good, it’ll be like, ‘Yo, I see you, I see the vision.’ ”

Tatum contends that there was always plenty of style in the tunnel, and social media merely made the ’fits visible. Perhaps. But not everything social media makes visible goes viral, and not everything that goes viral gets fashion’s stamp of approval. Fashion chooses its muses with care. Designers respond to a certain type of admiration—to whatever feels paradigmatically now. That’s how you wind up with Prada dressing Caitlin Clark for the WNBA Draft. And that’s how I—lifelong non-sports fan—wind up tuning into basketball games and following Clark’s rival Angel Reese on Instagram. It’s not just because I enjoy tracking her evolution from upstart Bayou Barbie to Met Gala jet-setter. I’ve seen versions of that Cinderella story before. There’s something about Angel Reese, or about what Angel Reese represents, that means more to me.

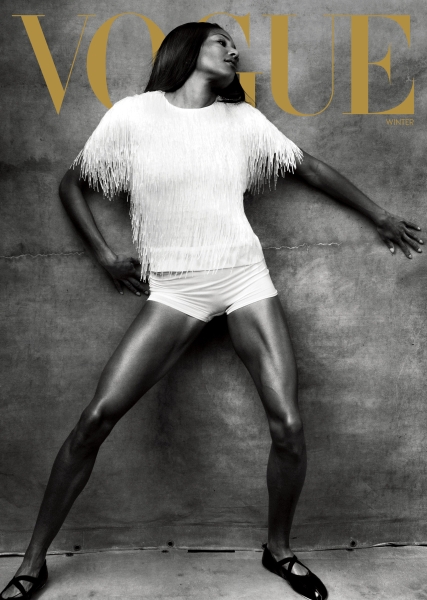

On a brisk New York morning, I catch up with Reese as she’s passing through the city, and sit in on a training session. Her sophomore season with the Chicago Sky is some months off, and this is her time to work on technique. Again and again, she tosses the ball into the basket, with a near metronomic rhythm. From the free throw line. From the side, off one leg. Catching the ball on the go and sliding into position: bend and stretch, eyes on the target, a light touch, ball whirling upward, swish. Then again.

“It’s always been both: basketball and fashion,” Reese says. Basketball runs in the family, she explains; both her mother and grandmother played. And when she was growing up in Baltimore, the sport was just around. “But I was a fashion girlie from young too. Like—let me find this picture my mom sent,” she goes on, digging through her bag for a snapshot of herself, age five, adorable in a pink dress and tiara, almond eyes gleaming. “I was always in my mom’s closet, putting on her stuff. I liked to carry a purse. Hair done. I wanted to look put together. I still do.” That desire to look finished applies on and off the court: Reese earned her Bayou Barbie nickname at Louisiana State thanks to her penchant for glamming up for games.

“I used to watch America’s Next Top Model with Tyra and practice my walk in the living room,” Reese recalls. Later, in college, she put that sashay to use in the LSU tunnel, with her teammates joining her in serving fierce pregame looks. Once on the court, she led them to a national championship before deciding to go pro—an announcement she made not on ESPN but rather via this very title. One day, she says, she’d like to model in a real fashion show; maybe Paris Fashion Week, that’s still on her to-do list. In the meantime, however: eyes on the target, a light touch, swish. Again and again and again. I record her with my phone, a minute or so of rote grace and precision, then zoom in on her eyes, all steely focus under unblinking false eyelashes.

When I was growing up in the ’90s, I didn’t know fashion, but I knew sport, and I knew Nike, because they had people who looked like me in their ads,” says Off-White creative director IB Kamara, who hails from Sierra Leone. “It’s very democratic in that way. And very global. You can be a kid anywhere in the world and be a fan of a team like AC Milan, and that jersey will mean something to you.” Off-White recently capped a three-year partnership with AC Milan by launching a capsule collection celebrating the storied football club’s 125th anniversary. A similar collaboration with the WNBA’s New York Liberty debuted last fall, and likewise comprises merch for both players and fans, as well as a charitable component.

All of which is very much in keeping with Virgil Abloh’s vision for the brand. I recall a conversation I once had with Abloh, about a project he was working on with Nike, via Off-White—making uniforms for a soccer team of West African refugee kids in Paris. This was sometime early in 2017, and Abloh made a point about sports being a pastime and a passion we share across borders. That sometimes means a seed takes root in surprising soil: After civil war broke out in Sierra Leone, Kamara fled to Gambia…where, among other interests, he cultivated a childhood fixation on Serena Williams. “People don’t know this about me! I love her, I love tennis, I love watching it,” Kamara enthuses. “It’s so expressive. There’s so much personal style.”

Many Sierra Leoneans fled that brutal war, among them Alphina Kamara (no relation) and Constant Tiafoe. They found shelter in the United States, where their twin sons Franklin and Frances Tiafoe were born in 1998. Constant helped construct the USTA’s Junior Tennis Champions Center in College Park, Maryland, then signed on as the maintenance manager for the facility, a regional training hub for young tennis talent. “He worked constantly—he even slept at the club—and me and my brother, we’d stay with him.” So that’s how Frances Tiafoe stumbled on to the court; he lived there, basically. At 17, he won the USTA Junior National Championship.

Right from the get-go, Tiafoe was known for his passionate playing style. “And I wanted clothes to match, you know? Loud colors, bold colors, stuff that pops,” Tiafoe says. His favorite ensemble is probably the borderline psychedelic one his sponsor Nike designed for him to wear at the 2023 Australian Open. Suffice to say, his mental mood board is not collaged with vintage images of men in starchy tennis whites. “My influences originally—I’d say, I liked to look at awards shows, the BET Awards, and for real, the Met Gala. I liked to see these mega-mega celebrities when they were really turned out,” he says. “You know, going for it.”

If the Met Gala seems a far-flung source of inspiration for Tiafoe, consider that he sees himself as not just an athlete, but an entertainer. “Don’t get me wrong, I’m battling as hard as I can for every point. But what we do, what we put our bodies through, at the end of the day it’s in the service of entertaining people.” And fashion, Tiafoe believes, is part of the show. Offstage, he still tends to favor the baggy silhouettes of his youth, when he was taking most of his style cues from basketball. “Well, yeah, growing up, we all were, of course.”

“You can be a vessel, a shield; you can make armor,” says Ambush designer Yoon Ahn. “You empower them. That’s what fashion can do for sport”

Clothes matter in the NBA. A lot. How that came to be is a rather convoluted tale—but, in its abbreviated version, a very good lesson in the way formal limitations can enhance creative thinking.

At the start of the 2005–2006 season, then NBA commissioner David Stern instituted a dress code for players: “business” attire when participating in any team or league activities. This included, importantly, the walk through the tunnel from team bus to locker room. As Tatum explains, many players decried the dress code as racially motivated, because it specifically prohibited sports jerseys, “headgear of any kind,” and visible “chains, pendants, or medallions.” You may as well have drawn a giant X over a photo of Allen Iverson, with his signature bling, baggy clothes, and flat-brimmed caps and durags. “I thought he was stylish,” says Tatum, who looked up to Iverson as a child and paid attention to what he and other top players wore to games. “A lot of those guys, they came from the inner city, and that was how they expressed themselves—that hip-hop influence.” As a kid in St. Louis, Tatum was all about that look. “Air Force 1s, everything oversize—like that.” A far cry from an aesthetic he now describes as “sort of, luxury ‘business casual.’ ”

“Love a cardigan, love a suit, a matching set, a collared shirt, a button-up,” Tatum elaborates.

What happened, basically, is that NBA players—once stuck with the dress code—embraced it. Stars like LeBron James, Dwyane Wade, and Russell Westbrook studied up on designers and the finer points of tailoring. The looks got sharper and splashier. Bit by bit, “the tunnel” became a promenade of dandies the likes of which hadn’t been seen since Beau Brummell strode the cobblestones of Mayfair. After Stern retired in 2014, the code was relaxed, allowing for progressively zanier ’fits. Meanwhile, young athletes like Tiafoe, Tatum, and Reese were imbibing an avalanche of fashion content (every NBA team plays 82 regular season games) and witnessing the utility of style as a personal branding tool.

NFL players were paying attention too. They wanted their own tunnel. Or some of them did, anyway—Odell Beckham Jr., Cam Newton, a handful of others. Then more. “It’s very new,” says Kyle Smith, the NFL’s recently appointed in-house fashion editor. “When I started working as a stylist for the NFL Network in 2019, nobody talked about what the players were wearing. Because mostly they were wearing, you know, whatever. Sometimes there’d be a flashy suit, and that would surprise people.” Today, the NFL is actively boosting its swagged-out fashion scene, launching its own style-focused Instagram—one of several new initiatives led by Smith—and broadcasting pregame interviews to showcase the ’fits of clotheshorse stars like Cincinnati Bengals quarterback Joe Burrow.

“As an agent, one thing you always impress on your clients is that there is inherent value in being seen and being respected outside your sport,” explains Tom Chapman, a partner at mega-agency WME Sports, which represents Tiafoe, among many others. “So how do you do that? If you want to build a persona that lasts past what—let’s face it—can be a very short career, fashion can help. So players are investing more and more into their look. And the NBA and the NFL, to their credit, they’ve done a great job giving them a platform, and it’s been good for everyone.

“So now we’re asking ourselves,” Chapman continues, “golf, tennis, other sports—how do they catch up with that? What do their tunnels look like?”

Smith was not, until a few years ago, a football fan. Sports in general, not his thing. He started his career assisting the celebrity stylist Karla Welch. It wasn’t until he happened to get a job dressing football players—which was, at first, “just a job”—that he began to think, Oh—this is interesting. He was struck by how extraordinarily hard these men worked. “And, like, 90 percent of them, you’d never recognize their faces, because they’re wearing helmets during the game, they’re just part of the team,” Smith notes. “I don’t know, it was refreshing.”

Likewise, designer Willy Chavarria had an ambivalent relationship to sport. “It interested me aesthetically,” he says. “I’ve always been obsessed with the way people dress to assimilate into different groups to express their identities—and team sports are such an example of that. Yankees, Lakers, whatever. In Chicano culture that’s a staple, an oversize football jersey. Doesn’t matter if you’ve ever watched a game.”

Cheeky versions of those jerseys showed up in Chavarria’s spring 2025 RTW show, which paid homage to America’s Chicano community. (Indeed, the name of the collection was América.) More sportiness was to be found in the debut of the Adidas Originals x Willy Chavarria collaboration that closed the show, with Olympian Noah Lyles serving as one of the models. The aesthetics of sport still interest Chavarria; now, the athletes interest him too.

“The thing about athletes, they’re not famous for nothing. You know? We’re so bombarded with that now, people where you’re like—who are you? Where did you come from? With social media, these ‘celebrities’ just kind of appear. Whereas,” Chavarria notes, “when you see someone who can swim faster than anyone else in the whole world, it’s like—wow, you’re incredible.”

Eyes on the target, light touch, swish. Repeat. I’ve watched that training video of Reese a bunch of times; there’s something hypnotic about it. What it doesn’t capture is the stuff that happens later, when Reese is tiring out and her shots start going awry. Then she gets exasperated, and she could call it quits, but she keeps shooting. Marshaling some inner reserve of—what? I’m not sure. And finds her rhythm again.

As Chavarria points out, we’ve been living through a rather strange epoch, fame-wise. For the past decade, maybe longer, the normal order of operations has been inverted: First you get followers on social media; then, once you’ve proven your influence, you branch into some other craft or calling. Be a model, an artist, a fashion designer, an entrepreneur. Run for office if you like. There was always a certain “fake it till you make it” aspect to this, but that was precisely the allure—the most successful influencers seemed to have discovered a cheat code for navigating a fast-evolving, culturally and economically disruptive technology. Bring on the filters.

Now we’re somewhere else. Awash in pseudoscience, misinformation, bots, deepfakes, AI-generated content garbage. Maybe I’m only speaking for myself here, but I long for the real. And when I watch eight Olympic sprinters set off at the women’s 200-meter final, and see Gabby Thomas streak away from the pack, I am in no doubt that that is what I am witnessing.

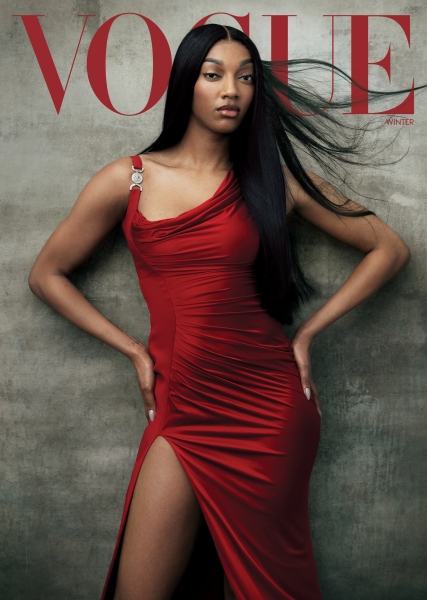

“There’s so much truth in what we do,” Thomas agrees, when I catch up with her last fall. She’s just returned from a long run, but she looks like she just returned from the spa—dewy-skinned, refreshed, no filter necessary. “On the track, I can’t cheat four years of hard work and commitment—otherwise I wouldn’t be there,” she continues, going on to note that any Olympic-caliber athlete has spent countless unpublicized hours mastering their sport. “You show up every day, and you work. And win or lose, the emotions that come—you can’t fake that, either.”

Since returning from Paris with three gold medals, Thomas has taken in fashion shows and basketball games, done some modeling, and presented the CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund award last year. If Gabby Thomas is turning into an influencer, I, for one, am prepared to be influenced. She’s smart, charismatic, and seems to be having some well-deserved fun in the interval between the hard work she put in to earn her fame as a sprinter, and the hard work to come in the medical field where her ultimate ambitions lie. (Thomas studied neurobiology and global health at Harvard and has a master’s degree in epidemiology.) Fashion, she says, is one of the things she’s enjoying right now.

“I’ve been so in athlete-world, I feel like I’m just starting to get a sense of what I like,” Thomas says. “Not that I don’t have my own style. I do, but then I put on something like that white Carolina Herrera dress that I wore to the show, and it’s like, Oh, oh-kaay. Since then I’ve been doing more ‘pretty’ looks. And more polished. Same with the hair and makeup, I’m growing with that too.” Listening to Thomas talk, I’m reminded of a comment Chavarria made about her Olympic teammate Lyles—a fashion fanatic who, at one point, was angling to get a track-and-field “tunnel” going.

“At the end of the day, even if he likes going on a red carpet, you know his priorities are elsewhere,” said Chavarria. “Which is cool.”

“I will never take my daughter to watch robots play tennis.” So swears Alexis Ohanian, husband of Serena Williams, a cofounder of Reddit, and, under the auspices of his venture capital firm Seven Seven Six, creator of the women’s-only track invitational Athlos, which he launched with Thomas’s help in September. Ohanian and I had been chatting about his investments into women’s sports—there are several; he plans more—and found ourselves in conceptual territory. Sport, we theorized, was the anti-virtual. Not merely because, as the philosopher Avishai Margalit wrote, “watching excellence in sports is watching humans in their fullest expression”—gratifying, at a moment when AI seems ever more humanlike—but also because a sporting event is one of the few occasions left where we watch in real time and gather together in physical space, be it stadium, sports bar, or friend’s sofa. And where else—as several people pointed out to me in the course of reporting this story—do Americans estranged from each other manage to find common ground? “Share a beer, share a cheer,” is how Ohanian put the ethos. Which is, at least, a step in the right direction.

“The thing with sports is it’s constant. You go to any bar anywhere in America—anywhere in the world—there are sports on,” notes WME Sports agent Chapman. “It’s not like the cinema or music; that’s selective, that’s taste. Sports is just kind of there. In theory, it’s for everybody.”

If you want to be cynical, you could say that the fashion industry is glomming on to sports, and its stars, because that’s the last means of communicating to a wide audience. Designers see Reese, they see Tatum, they see dollar signs. Sure. But isn’t the cynical explanation also the Pollyanna one? Why wouldn’t the fashion industry want to be in business with people who represent the values of hard work and authenticity? Who give us, at a moment when many of us find this rather difficult, something to believe in?

“I feel like we got to represent the best of America,” Thomas says to me, reflecting on her Olympics experience. “Focused on what brings us together—our dedication, our resilience, our passion for what we do. I felt pride, pride for my country.”

And on the flip side, as someone who loves fashion, I believe it has more to offer athletes than help with their personal brands. Consider the frilled and bow-bedecked looks Naomi Osaka wore when she made her comeback at last year’s US Open. According to Yoon Ahn, the Ambush designer who collaborated with Osaka and Nike to create the head-turning ensembles, brainstorming began two years ago, not long after Osaka gave birth. She talked to Ahn about motherhood, about wanting to connect to her Japanese roots, about the pressures of professional tennis. “I wanted to give her an outfit that got her away from the pressure,” Ahn explains, “and made her feel like a little girl again walking out on to the court.

“You can be a vessel, you can be a shield; you can make armor,” Ahn goes on. “You empower them. That’s what fashion can do for sport.”

In this story: For Reese: hair, Lacy Redway; makeup, Susie Sobol; manicurist, Nori Yamanaka; tailor, Curie Choi. For Thomas: hair, Mideyah Parker; makeup, Janessa Paré; manicurist, Nori Yamanaka; tailor, Cha Cha Zutic. For Tiafoe: grooming, Valissa Yoe; tailor, Cynthia Crusan-Noble. Produced by Boom Productions. Set Coordinator: JoJo Roy.

The Winter issue is here. Subscribe to Vogue for $3 $1/month.