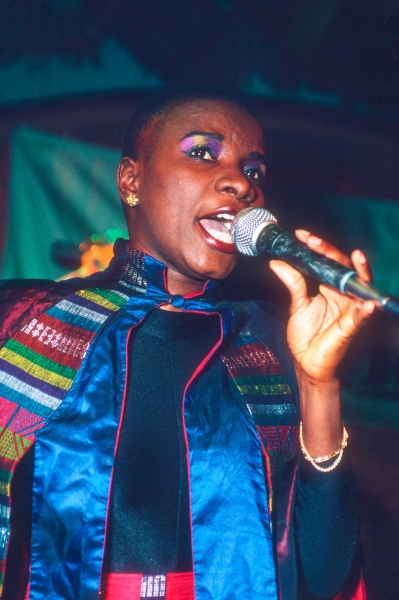

Late last year, I hopped on a train from Philadelphia to Washington, DC, to see a living legend perform with the National Symphony Orchestra at the Kennedy Center. Angélique Kidjo, 64, the Beninese musician, is Africa’s most well-known global artist. She’s won five Grammys (and been nominated 15 times) and has toured the world several times over. Time called her “Africa’s premier diva” in 2007; NPR described her in 2013 as “Africa’s greatest living diva.”

Kidjo’s been in the industry for 40 years, but she burst onto the global stage when she released her first international album, Parakou, 35 years ago. That night at the Kennedy Center, in an auditorium packed with people of all ages, races, and nationalities, she did what she’s done for decades: She showed the richness and vastness of African music, singing music from her own catalogue and covering artists including Fela Kuti, Miriam Makeba, and Burna Boy. As I watched her float across the stage, seamlessly weaving her way through half a century of African music from across the continent, I was amazed by how comprehensively she delivered a lesson in the depth of African music and culture.

When it comes to popularizing African sounds and culture, you used to be able to look just to Kidjo and a handful of other artists. In 2024, Kidjo was in good company. Thinking back on the biggest cultural moments of 2024, it’s hard to ignore the many African women who were at the center of it all, from the Grammys to the Met Gala and the Olympics. Just a few highlights: In February, Tyla took home the first Best African Music Performance Grammy for her viral pop hit, “Water.” At the Met Gala three months later, she turned heads when she arrived in a custom Balmain dress that transformed her into a sand sculpture. After working with Rihanna, Beyoncé, and Drake, Tems dropped her long-awaited soulful debut album Born in the Wild. At the Olympics, Aya Nakamura, who was born in Mali and raised in France, took center stage for the Opening Ceremony. Ayra Starr—who sings in English, Yoruba, Nigerian Pidgin, and French—dropped her sophomore album, before going on to dominate the festival circuit all summer.

Thinking back on the biggest cultural moments of 2024, it’s hard to ignore the many African women who were at the center of it all.

Over the past decade, global African music has been dominated by Afrobeats, the catchy rhythms popularized most by Burna Boy, Wizkid, and Davido. Though some women succeeded, including “queen of Afrobeats” Tiwa Savage, the genre was dominated by men. In recent years, a new crop of female artists has emerged and with them, a mix of sounds—from Starr’s pop sound to Tems’s sultry R&B-adjacent sounds, to Tyla’s clubby Amapiano. Their ascendance in pop culture reminded us that there is no one way to sound or be African.

“African music can be pop music too,” said Tyla, when she received the MTV Video Music Award for the best Afrobeats song in September. The comment was perceived by many as a dismissal of the genre, but Tyla was making the point that there’s more to Africa’s music scenes than Afrobeats. One could easily mistake a Tyla song for a pop song by any American pop singer. Elsewhere, Tiwa Savage ventured into film, directing and starring in Water and Garri. Lupita Nyong’o dove into telling African stories with her podcast “Mind Your Own.” These projects all pushed back on what Western institutions have decided Africanness is.

In many ways, it feels somewhat ridiculous to point out that, just because a group of singers comes from a single continent, their sound and viewpoints will not be identical. (How absurd it would be to say the same of a singer from Portugal and a singer from Poland.) But the simple fact is that performers from Africa are too often painted with too broad a brush. On the flip side, their varying backgrounds have historically been lost. Look at the furor that surrounded Tyla describing herself as “colored,” which set off a debate in the US, where the term is derogatory; in the context of South Africa, the term means that someone is mixed. One could also look at the right-wing objections to the fact that Nakamura, with her African heritage, was asked to represent France at the Olympics; her detractors claimed she wasn’t French enough. In both instances, non-Africans wanted to reduce the women and their music to one part of their identity, when that simply isn’t what it means to be African in this day and age. And in both cases, they forced us to have tough conversations about nationality, race, and belonging.

With the 2025 Grammys just a month away and with Tems and Yemi Alade nominated, it’s worth celebrating the significant ways they and their peers broadened our consciousness last year. These women, whose music and identities blur genre and geographic boundaries gave us reason to engage more deeply with a part of the world whose identity has been defined by others for far too long.