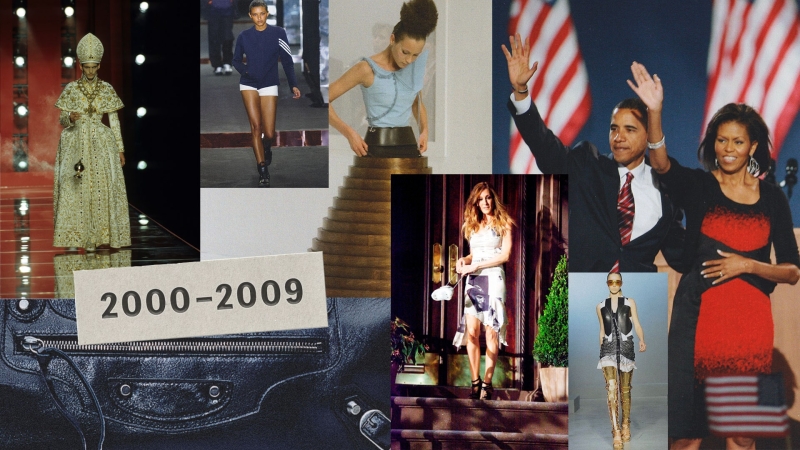

The year 2025 is almost here, which means we’re a quarter of the way through the 21st century. We’re in the business of looking ahead. (And next year is going to be a big one, with debuts at Celine, Givenchy, Tom Ford, and, presumably, Chanel, though we’re still waiting for confirmation on precisely whose debut it will be, plus the inevitable surprises, like Beyoncé turning up at Luar or John Galliano’s transporting Margiela Artisanal show last January, which we look forward to most of all.) But as the keepers of fashion’s most complete 21st century archive—what is Vogue Runway, after all, “but a kind of museum of images?”—we’re also well positioned to look back. And so, each weekday this December we’re deep-diving into a single year, pulling out agenda-setting collections, the most significant red carpet looks, and the innovations, trends, and It-items that shaped not just the industry, but how the world gets dressed. The jumping off point, the year 2000, is particularly important for Vogue Runway. It’s the year our predecessor Style.com was launched, precipitating shifts still impacting fashion to this day. And so that is where this story begins.—Nicole Phelps

“What Did We Do Before Style.com?” How the Site Changed Fashion Forever

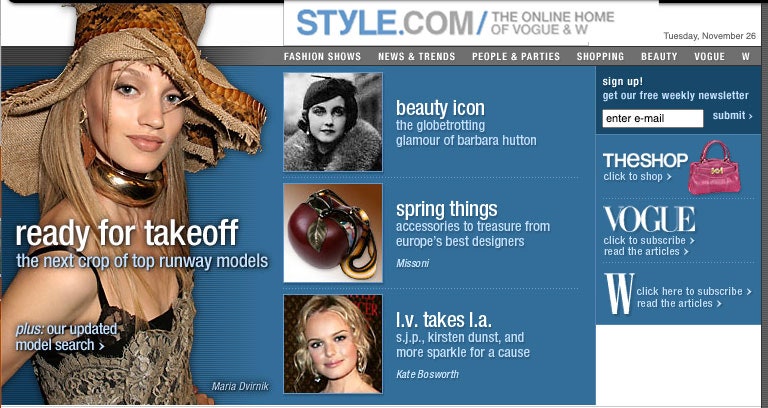

To say that Style.com “broke” the Internet isn’t horn-tooting, it’s a fact. The site revolutionized fashion show coverage, not just in terms of speed and scope, but also authority. However, collection coverage wasn’t its raison d’etre at the start.

Officially launched in September 2000 as “the online home of Vogue and W” magazines, the catchy domain was originally intended to be an umbrella site under which many brands would sit. “Our ambition is very simple: To bring the fashion authority of Condé Nast to the Web,” said a company spokesperson at the time. From the beginning, Style.com was conceived as a commerce site that would be actionable in a way that print wasn’t. “Advance’s effort may be the most ambitious yet by an established publisher to combine reading with retailing,” wrote Saul Hansell in a 2000 New York Times article. “The site soon will enable users to act upon those edicts [put forth by the magazines] by instantly buying the items they are told they must have. Think of it as point-and-click from the fashion clique.”

Designer fashion has always been aspirational; likewise, the system of presenting it has long been gated. Style.com is often credited with “democratizing” the fashion show, but it’s probably more accurate to say it provided access to invitation-only events and by extension to a world of surface glamour. Same-day reviews, backstage and details photography, and street style images helped give users a feeling of “being there.” It’s impossible to convey to digital natives what the pre-Internet before-times were like. I mean, broadband was just starting to replace dial-up connections! In any case, fashion hasn’t always been at the forefront of technology; Helmut Lang’s decision to present his fall 1998 collection via CD-ROM marked a tipping point. “It was a shock to the system, but a beginning of the new normal,” he later said. When Style.com launched two years later, not everyone was ready to embrace the brave new virtual world. Early on, a number of designers were wary of such exposure; status and copying were big issues. Soon, though, they’d be desperate to be reviewed (oh, the stories we could tell!) and within a very short space of time, celebrities, editors and stylists, and consumers alike were using the look numbers on Style.com as a kind of insider parlance.

It must be stressed how important it was that Style.com made complete shows available when the norm was to see only a few select outfits, the ones deemed worthy by editors. That shows were accessible all in one place and archived was also major. With additional features like search and moodboard, you could say that Style.com was a Gen-X proto-app that millennials were born into.

I came to the site from the museum world (The Museum at FIT, specifically), leaving behind a universe of materiality and objects, where time was thought of in years and eras, not seasons. At Style.com, instantaneity was the ideal and fashion was made of pixels, and thanks in large part to its influence, the image would soon become just as—or even more—important than the garment. It wasn’t Versace’s plunge-neck dress that went viral (before that was a term), it was the image of Jennifer Lopez in it. In fact, the popularity of the photo gave birth to Google Images; it also meant that fashion was becoming part of pop culture more quickly and reaching more people. The photos became a means through which insiders and outsiders could tell stories about themselves. Vogue Runway, launched in 2015, not only carries forward the mission of Style.com, but maintains its archive, which is essentially a kind of museum of images. Come to think of it, maybe my career change wasn’t as dramatic as I thought.—Laird Borrelli-Persson

Class of 2000: The Individualists

For its July 2000 issue, Vogue gathered 14 designers to be shot, class photo style, in New York by Steven Meisel, with Grace Coddington on styling duties. The designers chosen represented a new wave of talent transforming fashion, and boy, oh boy, were they well chosen. All were, in their own way, pretty darn revolutionary.

The designers were: Nicolas Ghesquière (back when he was at Balenciaga), Hussein Chalayan, Veronique Branquinho, Junya Watanabe, An Vandevorst and Filip Arickx of A.F. Vandevorst, Hedi Slimane (then at Dior Homme), Josephus Thimister, Olivier Theyskens, Lawrence Steele, Burberry Prorsum’s Roberto Menichetti, and Viktor Horsting and Rolf Snoeren of Viktor & Rolf. Collectively, they had upended heritage houses, moved conceptualism to center stage, radicalized silhouettes so that everyone would eventually wear them (hello, skinny jeans), shifted the axis of influence to some quite crucial degree to Belgium (though really it was all about someplace that wasn’t Milan or Paris or London), and generally did that thing that any emerging group of madly inventive designers should do: cast fashion entirely and utterly anew. They’re not the avant garde—they’re the New Guard was the message of Sally Singer’s excellent accompanying essay.

From the vantage point of 25 years later—typing those numbers seems less scary than saying a quarter-century, somehow—we know how their stories played out: Some went on to other iconic houses, others had to disband their labels, and one—Josephus Thimister—is, sadly, no longer with us. But looking at this group shot brings to mind a more contemporary thought: How would you do this photograph now—and who exactly would be in it?

The intervening years have pivoted the industry to a place where heritage houses owned by luxury conglomerates dominate in a way they didn’t back in 2000. Conversely, to be an influential independent designer is even harder to achieve now than it was back then. The Meisel image hints at what looked like perhaps a more even playing field. Creativity is still with us—and how—but this group shot, for all its wonderful prescience about incredible talents, is also a snapshot of a moment before everything changed.—Mark Holgate

The Dress That Launched a Thousand Internet Searches… And Google Images

The world worried that as the 1900s turned to the 2000s the “millennium bug” would crash the planet’s computer systems and create chaos. Thankfully, that didn’t happen. What nobody saw coming was that just two months later the combination of JLo and Versace would bring Y2K Google to the brink.

The fateful date was February 23, 2000. That was the night Jennifer Lopez hit the 42nd Grammy Awards wearing a Versace dress in green jungle print chiffon whose skirt was so split and neckline so deep it altered the history of the internet. As she came on stage to present the first award of the night you could hear the frequency of the audience hum go up a few notches. “This is the first time in five or six years that I’m sure that nobody is looking at me,” observed her co-presenter David Duchovny. Around 25 million viewers watched on CBS.

The next day that dress was a global talking point. Nobody had smartphones to check it out on, but as the word spread around the planet’s water coolers, people hit their computers to search for “JLo green dress.” Over in Palo Alto, the 18-month-old startup search engine Google took note as the volume of search queries stretched their servers to the max. As former CEO Eric Schmidt wrote in 2015: “Jennifer Lopez wore a green dress that, well, caught the world’s attention. At the time, it was the most popular search query we had ever seen. But we had no surefire way of getting users exactly what they wanted: JLo wearing that dress. Google Image Search was born.”

That photographic search function, now called Google Images, was launched in 2001 as a direct response to Donatella Versace’s design for Lopez. Fast forward to 2019, and the two reunited for a show in Milan that celebrated the anniversary of the dress that awoke the internet, and created one of the first landmark interactions between the fashion industry and tech. That night JLo wore a new version of the historic dress—and searches immediately spiked all over again.—Luke Leitch

Net-a-Porter Proves It’s Not About Being First, but About Being Best

As the millennium approached, the internet, still a nascent technology, was looked at with equal amounts of excitement and distrust. In the 1990s, the rise of personal computers and the invention of the web browser had given way to the so-called dot-com boom, where much like during the gold rush, people went crazy with possibility and new websites and online companies flourished—consider the fact that literally none existed before—and were rewarded with almost endless amounts of investment money. When the bubble inevitably burst in March of 2000, it seemed to reinforce the doubts that many had about the newfangled technology. At least where e-commerce was concerned, the 2000s kicked off with trepidation; Boo.com, a much ballyhooed online store aimed at young people, carried a mix of fashion and sports merch, and snazzy functionality that included 360-degree views of the garments and a virtual assistant (Miss Boo), that would aid customers with their shopping. Except it turned out that it was all a bit too snazzy, most computers were running on dial-up, which was too slow to load all the animations, and it also initially didn’t work on Macintosh computers. After only two years, and having spent $135 million dollars in investment cash, Boo was forced into bankruptcy.

It was into this ecosystem that LVMH launched eLuxury.com, which sold leather goods by Louis Vuitton, Marc Jacobs, and Fendi, among others, along with beauty essentials like face cream from La Prairie. Around the same time, Natalie Massenet, a former fashion editor, launched Net-a-Porter in 2000, although success didn’t come at once, she slowly built a steady base thanks in part to many of the fashion contacts she had made working in magazines. While eLuxury didn’t survive the decade, by 2005, Massenet’s Net-a-Porter was reporting sales of $16 million, and has since gone on to become the online store that set the precedent for every other store that followed it. The secret likely boils down Massenet’s editorial point of view: she curated Net-a-Porter’s homepage just like the shopping pages of a fashion magazine, highlighting trends but also breaking them down in an approachable manner. Add to that, above-and-beyond customer service that allowed literal first-time online shoppers to take a chance on buying something, knowing that they could easily return it without worrying or incurring extra charges. At the same time, because luxury labels themselves weren’t rushing to join the digital sphere, Net-a-Porter was able to capture the clientele from many brands. As fashion and technology continued evolving, so did Net-a-Porter: a year before Alexander McQueen streamed the legendary “Plato’s Atlantis” collection online, he had staged a mini-runway show for the pre-spring 2009 collection, that was immediately available for purchase and delivered within a day to most locations. A decade later, Net-A-Porter had gone from upstart to establishment; Massenet sold a majority stake to Richemont for £50 million.—Laia Garcia-Furtado

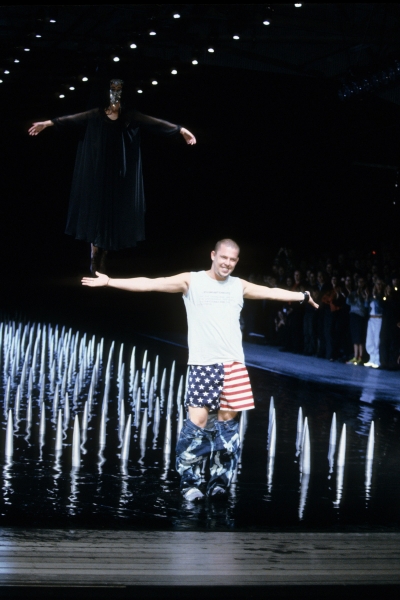

When Is a Coffee Table Not a Coffee Table?

Hussein Chalayan had already given the fashion industry one of its most searing images when he dressed models in chadors in an examination of Islamic women’s status in society. And he would go on to develop virtuoso dresses that morphed in front of his audience’s eyes, decade-hopping to a soundtrack of the 20th century that included “the ranting of Hitler, aerial bombing, jet engines, and the beating of helicopter rotors,” as Vogue Runway’s Sarah Mower remembers. Chalayan earned his avant-gardist reputation season-in and season-out, but the one that most completely captured his provocateur’s spirit was fall 2000, when he created furniture-as-fashion. I was in the room, a baby editor at Elle Magazine, and watched as four armchair slipcovers were converted into shift dresses by the models who would slip into them. Then Natalia Semanova stepped into the coffee table and it transformed into a skirt, a remarkable feat of engineering that no one, including the designer himself, was sure would come off until it did. Chalayan is a Turkish Cypriot and his mother experienced the fear of displacement during armed conflict in the 1970s. This show’s ingenuity and subtly pointed social commentary set a high bar that few of his peers have neared in the nearly 25 years since.—Nicole Phelps

The Shows of the YearMost Memorable Red-Carpet Moments

A Parting Shot