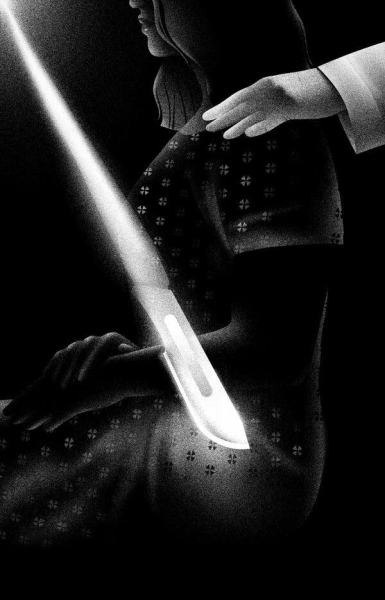

Patients often are in the dark about which organs remain and which were removed — particularly the ovaries, which profoundly influence lifelong health.

Patients often are in the dark about which organs remain and which were removed — particularly the ovaries, which profoundly influence lifelong health.

Listen to this article · 16:07 min Learn more

Stacia Alexander was 25 and pregnant when her OB-GYN first recommended a hysterectomy. It was 1996, and an ultrasound had revealed fibroids growing in the walls of her uterus.

But she knew what the procedure had done to her mother: After her ovaries and uterus were removed in her 40s, her mother faded into a sad, irritable shadow of herself.

So after giving birth, Dr. Alexander opted for surgery to prune back the fibroids. Years later, when the growths returned, she was again able to avoid a hysterectomy by choosing a uterine ablation, in which the lining of the uterus is burned away to prevent bleeding caused by fibroids.

But by the time she was 45, the fibroids were back, and her doctor informed her that she was “too old” for another uterus-sparing surgery.

Dr. Alexander, a psychotherapist in Dallas, was already on the operating table when a surgeon came in and asked whether she wanted a “full” or “partial” hysterectomy.

If she chose the second option, he warned, there would be no guarantee that she wouldn’t be back for another operation in two years. So Dr. Alexander agreed to a “full” hysterectomy.