Contents

- 1 Tracey Africa Norman On Her Fashion Industry Roots

- 2 Juliana Huxtable On Breaking Into the Arts and Media

- 3 Tracey Africa Norman On the Barriers She Faced

- 4 Raquel Willis and Tracey Africa Norman On the Struggles of Being a Trans Woman

- 5 Juliana Huxtable On the Power Dynamics of Being Trans in Fashion

- 6 Tracey Africa Norman On the Label “Transgender”

- 7 Juliana Huxtable On How She Hopes the Fashion Industry Evolves

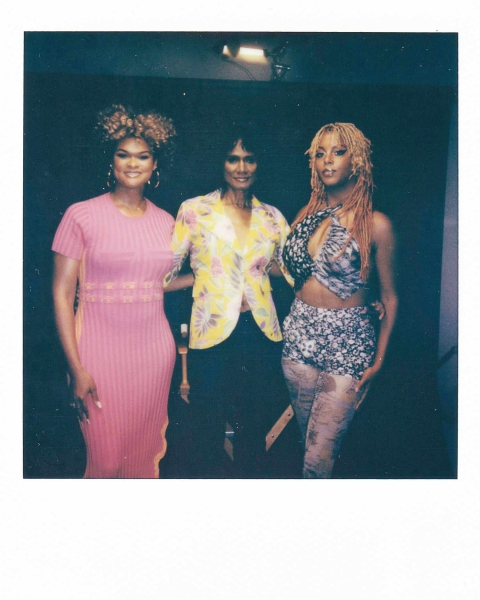

In collaboration with GLAAD, Raquel Willis, Tracey Africa Norman, and Juliana Huxtable sit down for an insightful roundtable discussion.

It's rare to see three Trans women share the spotlight in the mainstream media. Sure, Trans artists have appeared in TV shows like Pose and Euphoria, campaigns for Marc Jacobs and J.W. Anderson, high fashion magazine covers, and the music videos of pop stars like Charli XCX and Taylor Swift. But the reality is that Trans women—especially in the fashion industry—are often tokenized, booked to fill a quota or check a box on a progressive, proverbial to-do list. Not often are women of this experience given a raw, unfiltered platform to air out the joys, hardships, and titillating stories that come with being Trans.

In May, InStyle collaborated with GLAAD to host Raquel Willis, Juliana Huxtable, and Tracey Africa Norman for an unfiltered, filmed discussion by Trans women and for Trans women.

A little bit about these trailblazers: Willis, the discussion’s moderator, is an acclaimed activist and writer, the author of a memoir titled The Risk It Takes to Bloom and the former Executive Editor of Out; Huxtable is a multi-hyphenate artist whose work has appeared in the Museum of Modern Art and the New Museum, and who has modeled for brands like Eckhaus Latta and Kenzo; and Norman, the first woman of her experience to have a big break in the modeling industry, appeared on a Clairol box in the ’70s and in fashion editorials for Essence, Vogue Italia, and Harper’s Bazaar India.

All three women share different relationships to fashion, gender, and the intersection of the two. Norman, who in the video poignantly states, "I don't identify as Trans; I identify as a woman," describes being outed for her "sexuality" during a fashion shoot in the 1980s, a harrowing experience that put a halt on her blossoming career. Huxtable speaks about the tokenization of Trans women in the fashion industry. And Willis elegantly guides the discussion to acknowledge the discrimination all three participants have faced not only for being Trans, but also for being Black.

Above, watch the full conversation between these pioneers, and, below, scan for edited, condensed excerpts from Willis, Huxtable, and Norman's discussion.

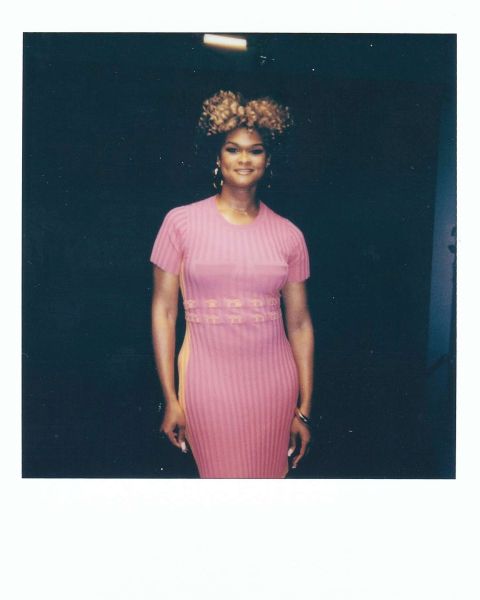

Tracey Africa Norman On Her Fashion Industry Roots

"What started me doing fashion was a friend of mine who I knew before my transition. It took a few years. I had separated from that group of people because I was doing my thing and I didn't know how they would accept it, so I just became the woman that I am today.

I was downtown in my city of Newark, and I ran into the friend who came out of the store. He recognized me. I guess he heard through the grapevine what my new name was, and so we had a conversation, and he was checking me out and he was saying, 'You look really beautiful. You should think about modeling.' I was like, 'Okay.' From that moment on, there were local designers, local makeup people, and I started working with them and that's where my training started, in Newark.”

Juliana Huxtable On Breaking Into the Arts and Media

"I've always loved art, but art in a total sense. And so I feel like that's always encompassed multiple things. I've loved fashion since I was a kid. When I was three, I declared that I was going to be a poet and a painter to my parents. And then at some point I thought I was going to be a fashion designer, but I would cycle through so many different imaginations of what I could be, I think because, obviously, it's hard for me to pick a single thing. I didn't study art or fashion, I studied literature and gender studies.

I moved to New York and I was working at the ACLU. My distraction when I had downtime at my job, when I would have a lunch break or something … I would just get on Tumblr, Tumblr and digital communities, which have always been something that I’ve been drawn to…

I built an audience by just sharing my thoughts, sharing early sketches, sharing early images. That's really how everything started. I think what I loved about blogging and the digital world is that if I didn't see it in the world, I could just make it myself and I used myself as the means for that. My first modeling gigs were just out of people following me and being like, 'Oh, you have a cool sense of style.' My first writing gigs, art stuff, it all came from people who had either followed me, what I was doing online, or that had found out about me through someone that did that."

Tracey Africa Norman On the Barriers She Faced

"Back then, in the '70s and '80s, there weren't names for us. In the ball community, we were called femme queens. In the straight world, I was just Tracey Norman. I had this opportunity and my agency sent me out to Essence magazine. I worked for them for the first time and it went well. I met the photographer. I met the stylist and the hair person. In fact, he came in after I got my makeup done. He came in and he was developing this makeup line called the Rasta Wig. Nobody knew that he had it on his head. It was this short Rasta that he had done, and he took it off of his head and put it on mine. When that happened on the set, they put this big choker on me, and that was a marriage ring to a specific tribe in Africa.

Then, the second time that I came was two years later, where I was literally on the set and I was in front of the camera taking photos, and the editor of Essence [Susan L. Taylor] was there, the photographer, the makeup artist, and two laypeople that was there helping the photographer—his assistants. As I'm taking my photos, the editor wanted me to pretend that I was Cleopatra sailing down the Nile. Once I got into character, I started getting tunnel vision. I was developing the character in my head, and I was actually feeling like I was on this boat sailing down the Nile, and the photographer was excited of what I was doing. The editor was excited of what I was doing, and she was telling me how beautiful the pictures are coming out. And then she said, 'Tracey, you got the best stare in the business'—I guess because I didn't blink while I was taking the photos.

As I'm still taking photos, all of a sudden a person comes in the left side of the room, because that's where the door was, the entrance of the studio, and then I instantly lost my tunnel vision on that side. It was like a fog. I'm looking at the camera, but it was like a fog on both sides, and I couldn't see to the left or the right, I was just focusing on the camera. It just felt negative, as soon as that person stepped into the room. At the time, I didn't know why. I started losing concentration, and that person called over the editor. They were having a conversation. The photographer saw me, that I was losing my concentration, so he told me to rest. So I did.

I got out of my position that I was in to rest and relax in the chair. At some point, I did glance to my left to see who was there, and it was one of the hair people from the first photoshoot. He was the one that came in and spoke to Susan. And then Susan went over to the photographer, spoke to the photographer, and she was looking at me on set. Then she looked in the photo box, looking at me, looking at the photo box, and then said, 'Tracey, I think we have it.' Prior to that person coming into the room, she told me that the pictures were so beautiful that she feels as though they could be the cover of the holiday issue. And then the person comes in and then that's what happened.

With that happening, my work literally stopped overnight.

When I made my phone call to see what I had to do that day—work, a test, whatever it was, or come in for a meeting—nothing for the whole week, nothing. Eventually, that Friday, they called me in and said, 'Could you come in because Zoli [the Zoli Agency] wishes to speak to you on Monday.' So we had a meeting. And then he came up with an excuse to not represent me anymore. They never approached me. Essence never approached me about my sexuality. My agent didn't approach me about my sexuality. They just believed, and that was the end of my career, as far as that particular time in my life. That was back in '83."

Raquel Willis and Tracey Africa Norman On the Struggles of Being a Trans Woman

RW: "It's still not easy for a Black Trans woman to just try and have a career, really, in any industry.

TN: It's true.

RW: Especially if you’re not seeking out to be an activist or an organizer. I think maybe that’s a little bit of our [Willis and Juliana Huxtable’s] saving grace, is we had that foundation in our work where we had community to fall back on, but we also had a career in the advocacy world. You were at the ACLU, me at places like Transgender Law Center, and on and on.

But what if you just want to be the supermodel that you are, or you want to be the artist or the musician and not have to answer all of these questions and hold everyone else's baggage around your identity?

TN: I don't think that's possible for us."

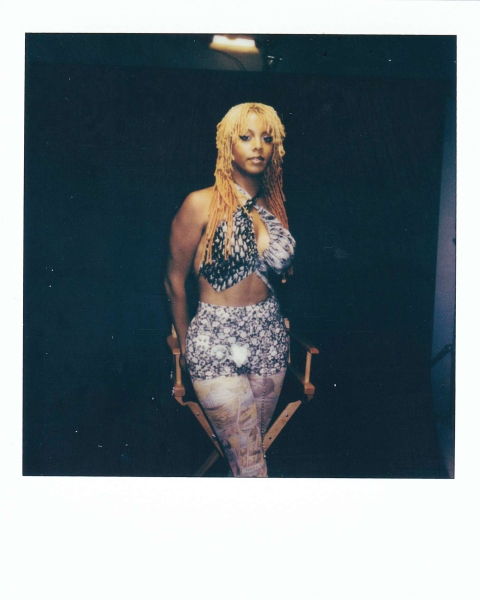

Juliana Huxtable On the Power Dynamics of Being Trans in Fashion

"I think I can relate to what Tracey was saying about, at a certain point, having a sense of distrust. I started all of my multiple career trajectories before being Trans wasn’t really a thing, or at least a thing to the degree where it's, like, every person has an opinion on it, every person is thinking about this term. It's supercharged. I remember getting booked. I was lucky because of pioneers like Tracey. I was able to never have to be in the closet or hide my Transness. But that's very different than being brought in because of your Transness. For me, particularly, making figurative work that uses representations of myself and representations of people, and also working in fashion, I was doing both of them concurrently and I remember this feeling when, then, it's like the booking started to shift.

At a certain point, it's like, 'You have a really interesting look. We love your look. Let's come in.' I always have a specific makeup aesthetic, people would book me for that, or I had different hair, or my style or whatever. That era was really great for me. But then, as there was a public desire to use Transness to symbolize progress, I remember getting bookings where it's like, 'Are you booking me because you're interested in me or are you booking me because someone in your office is just manic and it's like, 'We need a Trans person. Get a Trans person now!'?

I remember this period of time where I was like, this is overwhelming. Also, there were times where you would go to castings and people would say things like, 'Oh, we thought you would look more Trans. It's like, 'What does that mean?' I consciously stopped taking a lot of work because of this sense of distrust where it's like, 'Am I just being used in a context that's not really being thought through? Am I going to be put in a context where I'm being fed to people that would want to harm me? Or am I being used in such a way that could stoke the increasing cultural inflammation surrounding what Trans people are or are not?'

At a certain point, what was important for me, regardless of what I do in art, or in any field for that matter, was to make sure that, yes, I'm a Trans person and I'm always aware of that. I'm aware that I'm a Black person. I'm so many things, but I want to take jobs, particularly jobs in representational fields that make sure that people have freedom to do multiple things. I don't want to reify the idea that my value is only because I'm a Trans person, and that's what's hot right now, because that's also unsustainable for a career. It's not helpful for Trans people to tokenize them in that way. Yeah, I worked through a lot of distrust and just like, 'What are the motivations of other people?' And then beyond that, 'What are the ramifications of how I'm being represented?'"

Tracey Africa Norman On the Label “Transgender”

“Even though I was doing those interviews [with New York magazine, Marie Claire South Africa, and more], as I discussed with you, I told all three interviewers that I don’t identify as Trans. I identify as a woman because that’s how I lived my life. I worked as a woman being a model. I understood the game when the magazines put Trans to my name, because seeing my photos, it made a difference in how people looked at me. It helped sales for them. It helped boost my recognition. I just played along and that’s how Trans became a thing for me.

Now, I'm more relaxed with the term. In the beginning, I wasn't, but then I understood because when I was outed, the difference between me back then, it was never heard of. And then me being a woman of color was really another level of not possible. Today's girls, you guys can out yourselves. People from my past had power over me as I was discussing that earlier with you, that they had the power to either blackmail me, which never happened, but to out me, which happened.

You girls have outed yourselves, so nobody had that power over you. I congratulate you for that, so you're able to live way more comfortable than I did. Because when my career was shooting through the roof because of [the] discovery of a famous photographer, that's when I got nervous. In the beginning, I was not nervous, I was just going with the flow. 'Ooh, wow. Hey, ooh, it's exciting. I'm traveling here, I'm going there. I'm shooting in magazines. Mommy, look, look, look.' But as my career started shooting through the roof, that's when I got really, really nervous of, 'Oh my God, is today the day?' I would say a prayer before I leave the house, 'Please, Lord, don't let anybody disrespect me, call me out of a name or try to embarrass me.' Every single day I would do that. I got relaxed for a second because in my mind, it was a job. It became a job, modeling, even though it's exciting, it became a job.

With my check from Clairol, I had gotten my first apartment on 70th and West End Avenue. I was like, 'Yes!' When I moved in, it was me, some clothes that I had and my fur baby, my dog, and that was my mentality at the time. I had rent to pay and a baby to feed. It didn't dawn on me until I started working a lot that this could possibly happen and I could lose all of this, and then it came to pass."

Juliana Huxtable On How She Hopes the Fashion Industry Evolves

"For me, I think it's really important that the desire to signify progress in representation and in images and in media is matched with changing the material conditions and progress within the larger structures that produce those images, because images themselves are not the same thing as transforming the world, even on just [the] industry level. I think this, because art is also so visual and I work in photography, that's why it was really important for me, I photograph myself.

When I photograph other people, I photograph them, I do the parts of what I do that are normally, like, there's some unnamed man behind a camera who's usually getting paid and then is presumed to have the ability to produce the actual images themselves—it was important for me to do that. What I would love to see in fashion, for example, is more meaningful diversity in all aspects. It would be great to see people that are in agencies or starting agencies, photographers, producers, production companies, so that across the board there's real representation of how the world is changing and is complexifying and really getting more diverse.

There are so many horrible things that happen on set. I remember when I was really doing modeling before my art stuff started taking off—there was years where that was my main source of income—and being alone on sets and having photographers try and ask to take naked photos of me that they could then sell and I would get a cut or something. Just really edgy stuff. Shoots in Paris where people are making the most unhinged comments about my skin color in rooms full of people and nobody says anything.

I would like to see things like that get better. Particularly with modeling, I feel lucky to be able to do this. I never want to be unself-aware about the context that I'm in, but it can be really intense. You're really vulnerable to so many dynamics that are in the structure that's producing the image that you are ultimately a part of. I think it would be really meaningful if all elements that go into the production of these images and the media would represent the same progress that is purportedly being signaled or represented. Sometimes that happens, sometimes it doesn't."