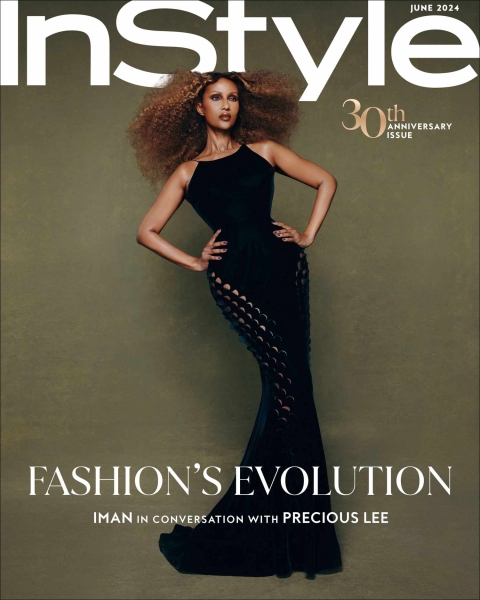

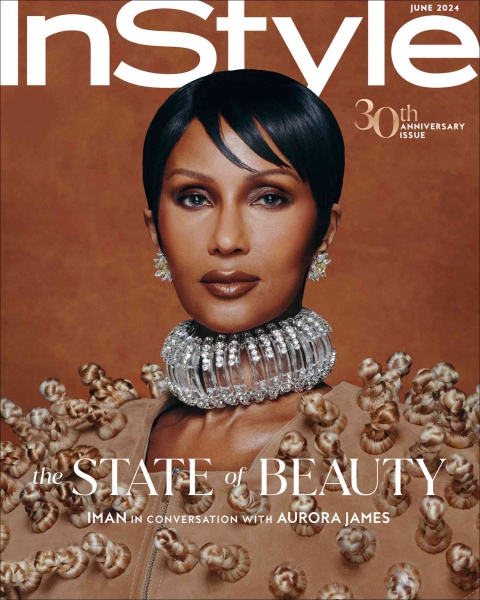

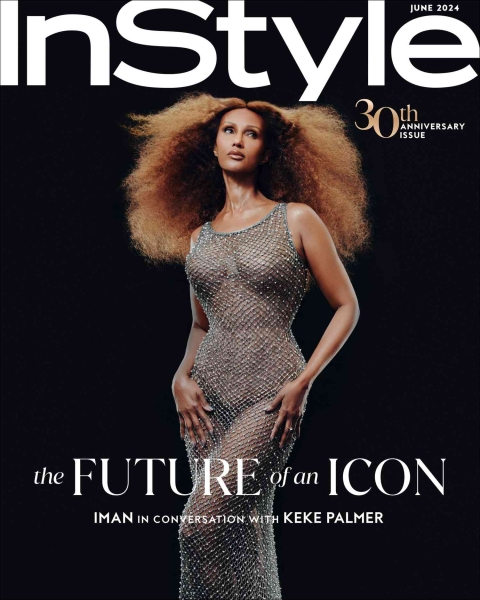

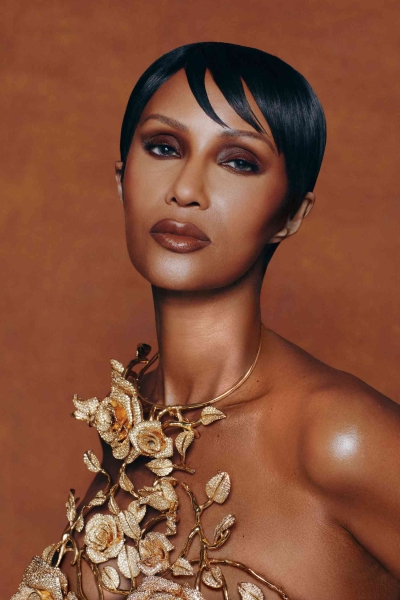

The supermodel, businesswoman, and activist in conversation with Precious Lee, Aurora James, and Keke Palmer.

What makes an icon? Is it a lengthy resumé filled with achievements and awards? Iman has that. Known first as a supermodel, she served for more than a decade as muse for designers including Thierry Mugler, Donna Karan, Yves Saint Laurent, and more; she’s authored a memoir and a beauty manual; acted in more than 20 projects; in 2021, she launched her first fragrance, Love Memoir, which is available on HSN, as is her clothing line, Global Chic.

Or is it that icon status achieved through volume of fans and followers? Iman has countless imitators (“It really touches your heart,” Iman says when asked by Keke Palmer what it’s like to see herself in other performers. “I have a lot of gay guys say, ‘I learned how to walk from you’”). She also has nearly 1 million followers on Instagram, her account peppered with aphorisms ranging from the poignant (“Do not exchange your dignity for popularity”) to the playful (“Normalize bringing dogs as a plus one”), delivered as though royal decree in color-blocked, all-caps text.

No, at its heart, being an icon is about impact. Iman is the Global Advocate for humanitarian organization CARE, which works to eradicate poverty and empower women and girls. She is an activist, using her fame and platform to bring attention to causes that matter to her, like the hardships refugees face or the lack of equality in the beauty and fashion space. She does this both by actively speaking out and by simply standing up for herself. But perhaps her most influential accomplishment is that she has helped women see themselves—in the pages of magazines and, through her groundbreaking beauty company, Iman Cosmetics, on store shelves.

As Iman recounted for each of our interviewers for this cover story, the idea for Iman Cosmetics—the first makeup collection specifically for all “women with skin of color”—was sparked during her very first modeling job, a photoshoot for Vogue in 1976: When she arrived on set, the makeup artist asked her if she brought her own foundation; when Iman said no, the makeup artist mixed-and-matched what shades he had. “I looked, literally, gray,” Iman recalls today. “I still say the gods of beauty were looking after me, because the photographs were black and white—that hides all sins.” Otherwise, she believes, her career would have been short-lived. "My image is my currency, so I better have control of that," she remembers thinking. Iman went shopping, buying any product that had a pigment close to her skin tone. She combined them herself and took Polaroids to see how the makeup would translate on film. From then on, she brought that self-made batch to every gig.

She launched her company 30 years ago with 16 foundation shades. “The idea was, at that time, ahead of its time,” she says. Blazing a trail is, for an icon like Iman, though, standard operating procedure. Here, she looks back on the influence she’s had and ahead to what change she might still impart through conversations with three women—model Precious Lee; designer and Fifteen Precent pledge founder Aurora James; and actress and television host Keke Palmer—who are, in their own ways, carrying her torch.

Precious Lee: There are so many different layers of inspiration that I have from you that aren’t just from the runway. So, the first question is: How has the fashion industry evolved or not evolved since you started modeling and what would you still like to change?

Iman: I came to America in 1975, around October, and I really started modeling in January, February 1976. I was completely unaware of this industry. I was majoring in political science in Kenya. I'd never seen a fashion magazine in my life. Never worn makeup or heels before I arrived here. So all this was foreign to me and I was 19 years old. And to see very small incremental changes within it through the years, and then big changes happen, needless to say, for different reasons, right?

In 2013, my friend Bethann Hardison called me. By then I was retired from modeling and I’d started Iman Cosmetics, so I really was not aware of what was going on on the runway. And she said to me, “Are you aware that they’re not using Black models on the runways at all?” And I said, “What do you mean? This is 2013.” And from then on, Naomi Campbell and Bethann and I started this conversation of putting a light on what was really transpiring—the absence of Black models on the runway. It got to the point that the New York Times even wrote an article saying, “Where are the Black models?” And then we highlighted the issue and took the case to the media. It didn’t stop just going to CNN or BBC or ABC. What was said there, it went on Instagram, and then all of a sudden, the Black communities and Black people and everybody started knowing what the issue is. And the change was instant, literally instant. Social media is an animal that is scary, but also if you use it right, it can work.

And that was 2013. The change was immediate and then it slacked back. But then Black Lives Matter and the murder of George Floyd happened, and that put real lights on all those dark shadows in our business. And then you saw, also, other changes happen in terms of hiring the right people. The change I saw in our industry, it was how many Black designers were all of a sudden given a position that they weren’t before.

Precious Lee: I did not know you had an interest in political science. Did you want to go into law?

Iman: My father was an ambassador, so I thought—and I'm my father's daughter, I'm so close to my dad, he passed away, but I was very close to my dad—so I thought That's the change I want to make. But then I regressed and became a model, and my parents were very disappointed in me, by the way.

Precious Lee: Well, not for long.

Iman: Not for long; I was able to take care of the family.

Precious Lee: I mention that because I was in school and I wanted to be an attorney. It’s wild [to be reminded of] the date when you guys started that initiative. I remember seeing it on BBC. That was the year that I moved to New York to model; I’d just finished school. So to hear what you're saying about being able to see that opening and then see it closed and see it opened up again… Because in 2020, as you know, is when—although I'd been there since 2013—I was a new face in 2020 and it was like an opening, a reveal, or removing this blanket that I felt.

Iman: You remember [at] the CFDA [event] that we were sitting next to each other, I told you… I mean, I remember the first time I saw you. I believe it was Versace, and boom, boom, this girl is coming. Tits jumping up and down. Now, that's a supermodel. And to me it is—when we talk about body positivity and all that, I didn't even look at it that way. When I saw you coming down that [runway], to me, that's a supermodel.

And you know what it takes for that to happen. Obviously it didn't start with me, Bethann, or Naomi. It was people who had done it before us. It's just the time, just push things forward and forward and forward. And I'll tell you, all hell broke loose—the murder of George Floyd, the Black Lives Matter [movement], all bets were off. And nobody wanted to hear, "Oh, I'm here for you." Well, how are you here for me?

Precious Lee: We need tangible [action]. There's so many conversations and actually seeing it executed is just a completely different ballgame.

Iman: Exactly. And that's what's called allyship. Allyship is when you move from conversation to action.

Precious Lee: What was the first show that you walked and how did the experience feel? Can you remember that moment? I remember right before Versace being like, This is it.

Iman: Exactly. This is it. My first show was for Halston. Talk about being put in an arena that you're not prepared [for]. I mean, I literally did not know anything. Halston had this studio, this very famous studio. The whole thing was a mirror. The walls were mirrored, the ceiling was mirrored, the floors were mirrored. I'd never worn heels in my life, scared to death. And [the show was] in his showroom. So it was like three rooms, all mirrored. I walked the first room, terrified, walked the second room, and now I got a little bit confident, and I thought, Oh, there is a third room. There are only two rooms. I walked right into a mirror.

Precious Lee: Oh my gosh.

Iman: After that, I didn't want to do shows.

Precious Lee: What do you think was the biggest challenge you faced in your career and how did you overcome that?

Iman: It’s speaking out. I came into the industry, although 19, but I was fully formed about my worth before I came in, as an African girl, Somali, coming from where I come from and all that. One thing that my parents instilled in me, especially as a girl, was that self-worth is key. And they said it to me: relationships, jobs, it doesn't matter—if it doesn't serve you well, it doesn't treat you well, just walk away from it. And walking away never means you're losing something. So I came in having that, at least, in my pocket.

The first thing that was thrown at me was that I wasn't going to be paid the same amount as the Caucasian models. And I was like, "Wait, what? And why?" And they were like, "Well, that's how it is; that's what the clients say." And I said, "Well, I'm not going to do this." And I walked away, literally. I told the agent, "I'm not interested in the Black and white issue. I am more interested in that if I am doing the same service that the white model is doing, I expect the same payment." And because I was able to walk away, I didn't work for three months, I said no to everything.

And then they came around and they paid me the same amount, and that changed the discrepancy. But you have to be able to walk away and it doesn't mean that your life is going to end. I didn't think my life was going to end at all. I thought I would find another job to [take care of] my parents, but I wasn't going to flip on this.

Precious Lee: Well, you were right. And that's a huge reason why you're the boss that you are now. And I think that because you came with that foundation from your upbringing—it's like you knew who you were on the soul level and it was not you attaching who you are to what you did. And that is something that a lot of girls, when they first start out, they don't know. I am really grateful that you took that stance. Who knew how long that would have continued to happen? Because a lot of people would've just been happy to be there.

Iman: They treat you the way they treat you, if you let them treat you that way.

Precious Lee: We as melanated people, there's this tenacity that, I think, is innate. And I just think it's so beautiful that you were able to hold on to that at that time. Because I know how it feels to be in that room and knowing how you're being scrutinized, especially you, having the goal to help your family. That's similar to how I started modeling. I was like, I guess this will pay for law school, great. But then when I realized the impact it [made when] people saw my image, it became a different machine.

Iman: It's like for me to see you and then to see Anok Yai or Adut [Akech], this is from one spectrum to the other. And what does that say about beauty? It's limitless. … Nobody ever said about Caucasian models, "Oh we have too many blondes, we have too many redheads." But they would say, "We only need one Black model." What? So to be able to see this, for me, is the fruit of our labor. And there were other people before me; let's not forget the Pat Clevelands, the Naomi Simses, who also were able to open that path for me to come through. And then you keep the door open, you don't close it behind you, you keep it open.

Precious Lee: You keep the door open.

I think the good times help the fight in the long run. So what is your favorite moment from modeling? I actually really hate when people ask me that.

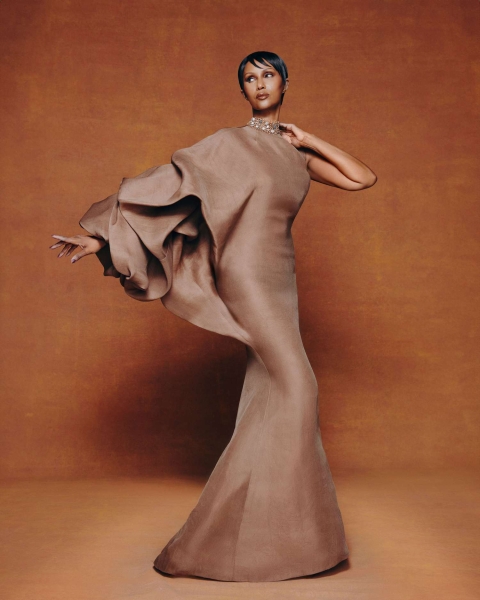

Iman: It's difficult. I would say the moment… In Paris everybody considered me classically elegant. And I'm not that all the time. And I met Thierry Mugler. Thierry Mugler saw something in me that I didn't even see in me. And he said, "I want to book you for my next season for the collections." And I remember coming back to New York and I thought to myself, When I go back, I'm going to do a new me.

In every show that I did before that time, all the hairdressers had no idea what to do with Black hair. So everything was a chignon. And then you see all the other models, they go from one show to the other and they look different. And you are like, Well, why can't that happen for us? I met a girl by chance, and her name was Ellin LaVar. I said to her, "When I go back to Paris next season, I want to do something different that I haven't done." And she started hair extensions on me and she experimented. I walked into Paris from a chignon girl to this full long—but curly. I told her I didn't want it straight, because I don't want to look like I want to look like a white girl.

Precious Lee: So it was big, almost teased out?

Iman: Yes. And curls. I walked in and Thierry was like, "Oh, where have you been all my life?" And all of a sudden my runway experience—between my hair, what he put me in, and just owning that—all of a sudden I was a new model, changed the game. And from then on I introduced Ellin LaVar to Tyra [Banks], to Naomi…. They were like, "How did you go from this to that?" "Here is her number. Call."

Precious Lee: The power of hair.

Iman: Especially for a Black model, because you feel like, If you pull my hair back all the time, how can I become a different person? Because modeling, that's what it is. We take personas, we become different people. We are acting in a silent movie.

Precious Lee: What is the best or worst career advice you've ever gotten and who gave it to you?

Iman: The best career advice I have gotten was probably Donna Karan. Donna Karan was with Anne Klein. And then she decided that she was going to leave and create her own brand. And her big show, I worked; I was one of the models. And one of the things that she said that I remember very clearly was, "I'm terrified starting this chapter on my own, but I have just designed the perfect seven pieces that only a woman can design." And obviously then it became one of the biggest shows and one of the biggest successes, but the advice that she was giving to all the girls is don't ever get afraid of getting out of your lane. There is no lane for you.

Aurora James: Iman, as you know very well, you are such an inspiration to me, but you're also such an inspiration to so many other Black female founders. And I am so curious—because when you started Iman Cosmetics, you had already had a modeling career—what was it for you that made you think, I absolutely have to take this leap of faith, get into an industry where there's actually no one else that looks like me, and I want to do it my way?

Iman: Well, the seed was implanted in my head on my first job for American Vogue in 1976 when a makeup artist asked me, and not a Caucasian model, who was also there, “Did you bring your own foundation?”

But I retired from modeling in 1989, and I had no idea what I wanted to do. I wanted to divorce myself from my industry so that then I could clearly think about what I really wanted to do next. So I said “no” to everything. And then I started thinking about this idea that always was there: the makeup, the makeup, the makeup. Then I started to think that I wanted to create Iman Cosmetics.

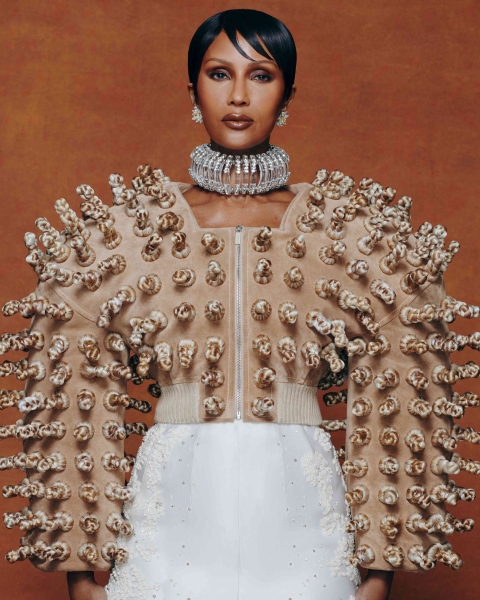

I started in 1992 after I got married and I came back from my honeymoon. I started formulating it in my head, what the philosophy behind it is. [Back] then “women of color” was just Black women. And the new language I wanted to use was “women with skin of color,” so it did not matter what your ethnic background is. You could be Thai, you could be Middle Eastern, you could be Brazilian, you could be Puerto Rican, you could be anybody, as long as you have a skin of color. So that was the language that the company was based upon, and that's how I created my cosmetics.

Aurora James: You were such an early pioneer, and it's so crazy to me because, honestly, even for me growing up—your product has always been amazing—but every one of the other brands, I still couldn't get a color match. And even today, the person that did my makeup this morning, we mixed a couple of colors. And I guess my question for you is: Since 2020, every makeup brand has diversified and added a lot more shades, but, genuinely, why do you think they just weren't doing it?

Iman: The word “racism” is thrown around easily, but what I could never understand from the big companies is: If their criteria is to make money, there is money to be made, there is a customer out there who needs products. And so it was very perplexing to me: Why were they so hesitant to create something that was suitable for our skin tone? Not an extension of what they already have, because just putting a pigment on something that you created for a blonde doesn't make it for a dark skin tone. They didn't understand the nuances. And they didn't really want to invest money in us. What they wanted is to benefit from us, but not invest.

The first thing that the big companies actually did was buy a lot of hair companies that were servicing Black women, because they knew if they just bought a company, they don't have to invest, they don't have to put the money in it because it's already built. They want to buy something, they don't want to create something. So that was the big difference. And what I wanted to create was— I wanted to celebrate the Fashion Fairs, the Naomi Sims, and all those that were created specifically for Black women, but I wanted to create it for a new generation of women. A new generation of thinking about what beauty is.

So one of the things that I created—and it was the first time it was created for women with skin of color—was bronzers. People were like, “What the hell is a bronzer for a skin of color?” And I was like, “You know Alek Wek, how dark she is? She can benefit from a bronzer.” It just makes your skin come alive. It's not a sun thing, it is what makes skin look luminous—and that's what they didn't understand.

I wanted to create something for a new generation of beauties that are coming, so that they don't look at themselves as “the others.” Because when you walk into a drugstore, you see the front, what [the retailers have deemed] the “general market,” which is the L’Oreals, the Revlons, and all that. And then through three aisles down in the back is what's created for Black women. So I fought so hard to be in that general market, because I wanted to create something that was really… She needs to see herself in there. Don't put us at the back of the bus again.

Aurora James: That makes me think about how you said at the Fifteen Percent Pledge Gala that if the Fifteen Percent Pledge had existed when you created Iman Cosmetics, you think it would've been a very different world for you. So I'd love to hear you talk about how your experience—even as someone who was already established and of a certain amount of means at that time—was really challenging, specifically as a Black female founder.

Iman: I have to say: I shut down Iman Cosmetics just at 2020. Maybe it was too early for me to shut it down. Because if I had Fifteen Percent Pledge, I'd probably be in more stores than I ever wanted to. So thank you for that.

But it was a constant battle. At the beginning, everybody was telling me, “Go to Macy's, go to Bloomingdale's.” I wanted a certain price point. “No, you have to bring the price point higher.” Trust me, we're all going to make more money if she can afford the product. And then the other thing was, “Why can't you just make it for Black women? Because the language is a little bit confusing.” I said, "It's confusing for you. It's not confusing for her." So it was that constant battle. Even to keep on the shelves the darker skin tones, foundations, it was a struggle because the stores would not order enough. They'd say, "Oh no, that doesn't sell." Well, it doesn't sell because you don't have it.

So before Fifteen Percent Pledge, before the murder of George Floyd, before Black Lives Matter came onto the scene, before lights were put in all the dark shadows of our business, before that, I just had enough.

And it was presented to me— companies, big companies wanted to buy the brand, [but] they wanted to keep the name for perpetuity. I would never have anything to do with it, and I couldn't live with that. I'd had enough friends in the fashion business that have lost their names. And thank God I have enough money that I didn't need to do that to my name and my brand, and so I shut it down.

Aurora James: You were so illuminating in Bethann Hardison's documentary, Invisible Beauty. I loved hearing you talk about how painful it was to see all of the progress that you guys had made within fashion only to have that rolled back. So much progress has happened since 2020; we're now in 2024, which is a whole new world. And I'm wondering: Does it feel to you similarly, like there's more progress that's being rolled back again? Do you feel like the progress that we've made will stay?

Iman: The word “activism” has to stay active. Because if it's not active, if it's not activated all the time, yes, all the progress that we make, it's rolled back. Because, yeah, I've given you the goodwill, but it's not goodwill. You know what I mean? Revolutions don't happen because one becomes enlightened. No. Revolutions happen because one is forced to change. So I think it shows to me how fragile it is, that it's like 10 steps forward, five steps back. So you'll say, "Oh, we didn't lose a lot." Yes, we have, if we've lost five steps.

When we talk about business, potential is universal, but opportunity is not. So it is that—the creating of the opportunity. Be an ally. I don't want anybody ever to say to me, "I don't see color." Yes, you do. We all do. But do not judge someone by that.

Aurora James: I’m so happy that you touched on allyship, because that’s something I think a lot about. I don’t know if you had a chance to see it yet, but last night in the 11th Circuit Court, they overturned the progress that had happened with the Fearless Fund, and they actually blocked them from being able to give grants out to Black women, which is crazy. And so my question for you is: How can the media, how can white people, how can even people of color be allies in this particular moment?

Iman: Yes, I did see it, and it was so disheartening. As I said, potential is universal, but opportunity is not. So if you're able to give some grants to somebody so that they can benefit from it… And mind you, let's not forget that, when I had Iman Cosmetics, as a refugee, I hired people. I'm an American citizen, but I am a refugee. I hire Americans. So to give grants to small businesses, to Black-owned businesses is actually beneficial for the whole government, for the whole system.

Aurora James: Totally.

Iman: I think this is where this allyship is very important. And then also, listen, we have a lot of money in Black businesses. We have a lot of celebrities who are Black who have a lot of money. And maybe this is their time to invest, too.

Aurora James: I agree. I think we have to really double down on supporting founders of color, specifically Black women, supporting the organizations that are under attack and who are helping give resources. Because you're exactly right. In America, we talk about the American dream. Someone gave me an analogy the other day: Everyone is born, there's a fence, and you tell those people to look over the fence. But if some people are born at six-feet-tall and another person is born at five-foot-two, you need to create a stepping stool for those people so that we can have an equal playing field to even be able to see over the fence.

Iman: And let's not forget, when it comes to women supporting women—this applies also in Africa, it applies in refugee camps and all that: When you support women, they support the whole community because they're the mothers, they're the ones who are taking care of the kids. So they're thinking about a whole community rather than just about themselves.

Keke Palmer: Obviously, you're an icon. I'm curious: When was it real to you? And what does it mean to you to be an icon?

Iman: I don't know what it really means. And you know this more than anybody else because you started in this business very young: Every time, it's a growth spurt. So, it's never like you get to a destination that you become an icon. And the definition continuously changes. But I've always kept it in my head that the minute that you start affecting and changing people's lives by just how you live, then you're an icon to them. I don't need to be an icon to many. I just need to be an icon to a few.

Keke Palmer: I love how you put that, because it's really about impact. When I think about being an icon—not myself, per se—but when I think about the concept of being an icon, I'm thinking about generations of people, you impacting generations, being an inspiration, representing and changing the way that people look at things. And we know that you've done that across the board, but for me, one of the coolest things growing up was becoming aware of Iman Cosmetics.

When you are a [front-of-camera] person, you do learn the business, because you are a brand. You know how to sell yourself. You know the value of marketing yourself, so you actually are strapped with the tools that you need to be a businesswoman. I'm wondering how easily or how quickly you were able to realize that, and what other things you had to learn to really step into that multi hyphenate space?

Iman: At the beginning, it was very difficult because I wanted to be the majority holder of my business so that nobody changes [things without my say]. They can’t say, "Oh, we don't have to have that many foundations because the dark skin tone doesn't sell."

I [understood] that I have to show up. I did a 15-city tour so that the people could meet me, and they could see that I was behind the brand, and it was not just that I was giving my name to somebody.

One of my favorite pictures from that time is of a little girl. She was barely six years old. She came—I had a table, I was giving a meet and greet, taking pictures and all that—and she just sat there on the table and had a whole conversation with me. And that's when I knew: That will be my future client. The politics of beauty, it has a very deep effect on identity.

Keke Palmer: Yes.

Iman: People need to see themselves in the right way, in the right place. [Certain retailers] didn't understand that kind of respect to a customer. So, where you place us, it's very, very important. The absence of Black models or Black beauties in magazines or in advertisements, it creates a whole self-esteem thing for our young girls. If they're only bombarded with images of a certain type, they think that that's beauty; that they are not beautiful. So, I was playing with that, and thank God I was majoring in political science, so I had some kind of a sense of how to play with that and made them understand that it's in [the retailers’] best interest to treat us right. Because money is money. It doesn't matter what color it is. It's always green.

Keke Palmer: The more well that I do, the more well we all do. And that's just the bottom line truth.

We talked a little bit about how you feel about being an icon and what that means to you, but the other side of that is fame, in general. How do you feel about fame? Do you like it? Do you wish that you could have a little bit more anonymity? I feel like there are pros and cons to it. I'm curious if you do, as well.

Iman: I would say the only pros I have ever seen is that when I have a very serious subject that I want to highlight—whether it's famine in Africa, whether it is the plight of refugees—then I have an audience. I can get an audience immediately. So, that's the only thing that I find that really lifts me up. The rest of it… I'm lucky enough to live in New York and especially in Soho; everybody in Soho is a star, or they think they are. So, nobody bothers me.

I have a very sweet recollection with young girls in Soho. I told this to Tyra many times, and she laughs her heart out. These girls were behind me. I think they were from NYU. They followed me: "Tyra, Tyra, Tyra, Tyra." I didn't pay attention to them. Then finally, one tapped me on the shoulder, and I turned around, and she said, "Are you Tyra?" I said, "No." And she said, "Oh my God. Are you Iman?" I said, "Yes." She said, "You look just like Tyra." I said, "No, she looks like me." And they thought I was dissing her. I said, "No, she's younger than I am. I was here first."

But when I talk about fame, it's like some days you are the pigeon, some days you're the statue.

Keke Palmer: What is your next act? You've done so many different things.

Iman: I'm now recuperating from foot surgery. So, I have been in bed for the past four weeks, and I have two weeks to go. During Covid, there were a lot of podcasts. Everybody had a podcast. People kept on telling me, "You should do a podcast. You should do a podcast."

Keke Palmer: Yes, you should, actually.

Iman: I don't want to. But lying here for four weeks, I thought to myself, I could do a podcast and actually just invite people to my bed and call it “In Bed with Iman.”

Keke Palmer: That would be such… Girl. You know why, Iman, that would be so awesome? Because you are so smart and so charming and so impactful that people would want to tell you everything.

Iman: There is nothing more revealing that you can get out of people than by being in bed with them. But I'm not going to do it. I'm not going to do it.

Keke Palmer: So, the next act for you, currently, just resting your foot?

Iman: Yeah, yeah. I'm open. I'm going to be 70 next year. I don't know what it is, but I know I'm going to do something else.

Keke Palmer: How will you know that that's the next thing? What is that feeling? What is that thought process?

Iman: During Covid, something happened. I was at my upstate house and I was by myself. So I started painting. My husband was a painter. My daughter is a painter. I have never painted. And I started painting. And one thing I learned from that—that I now apply to what my next act would be—is that I really didn't have to be good at it to just start. Always, we are in our own way: Oh, it looks awful. I might not be good, all that. I don't have to be good at it, I can just start painting. That curiosity and openness—with age that definitely comes because you're not obliged to satisfy people, in general. So, I think, that's the thing: Be open and be curious. You won't go anywhere if you're not curious.

Keke Palmer: So, this second-to-last question is for the reader, but also for me and for all the mothers out there: What has it been like throughout your career— Because for [women], it's just different than men. We have children. We have to carry them. It's a whole different process, especially when we are not just a working mom, but a working mom that is in the public eye. How did you learn to remove that guilt?

Iman: The guilt, unfortunately, we all suffer. We do. We do. But the guilt comes with the territory. So, just be graceful to ourselves and be kind to ourselves. I had my first child at 23 and my last child at 45, so I was completely two different mothers. So, my youngest has benefited that, at 45, I didn't have to work as much as when I was 23.

What I did with my youngest was if people come to me when I'm with her in public, I just say to them, "Please don't." If I'm in public, I'm Lexi's mom, I'm not Iman. And I'm hoping that they will understand that because a lot of them are parents.

One of the things I used to say to her was, “A deal breaker for me is lying. So, I don't care how bad things are, just tell me the truth. I can deal with that.” So, one day, we got home, and she went to her father, and she said, "Mom says ‘no lying,’ but she lied today." And he said, "What did she do?" She said, "We were outside, and this person came to her, and he said to her, 'Are you Iman?' And she said, 'No.'" And I said, "Well, because I'm not Iman when I'm with you. I'm Lexi's mom. So, that's not lying."

People expect [things] from you. They expect you to take a photograph with them, to look beautiful. They see you without makeup in the street with your kid, and they're like, Oh, she didn't look so good. Well, who cares? I'm with my kid. You can't satisfy everybody. You can't make everybody happy. And so, you just make yourself and your children happy.

Keke Palmer: I really receive that and appreciate that. Okay. The last question is… This is twofold: What do you want your legacy to be and whose legacy did you look at before your own?

Iman: The legacy that I looked up to before my own was my father. My father started as a teacher. He was fluent in Arabic. Him and my mom became activists. They were part of Somalia's—my country's—independence. And then we lost it all and crossed a country by foot, became refugees, but he was still the most elegant and kindest person ever. So, that's the legacy I looked up to: Regardless of whatever happens to you, you walk with dignity.

I'm just hoping that, maybe in public, my legacy will be that I've made others see themselves and become… I always say, "If beauty is in the eye of the beholder, let the beholder be you." You don't become beautiful because somebody told you. It has to start with you. The same about worth. I hope that all those young girls who saw me at work as a model and then a businesswoman and a spokesperson for refugees, that they saw there is something to be had in walking with grace, dignity, but always know your self-worth.

Credits

- Photographer

- AB+DM

- Director of Photography

- Jonathan Cortizo

- Brandon Scott Smith

- Stylist

- Jason Rembert

- Makeup Artist

- Keita Moore

- Makeup Assistant

- CT Hedden

- Anastasia Vavina

- Hair Stylist

- Hos

- Nails

- Arlene Hinckson

- Tailor

- Shirlee Idzakovich

- Cam Op

- Pete Keeling

- Gaffer

- Kyle Bedel

- Phil Nolan

- Booking

- Talent Connect Group