As Émile Zola captured it in his novel The Ladies’ Paradise, the 19th-century Parisian department store was one of the few places women could venture into unaccompanied. Some 50 years later, women in the United States were running those stories themselves.

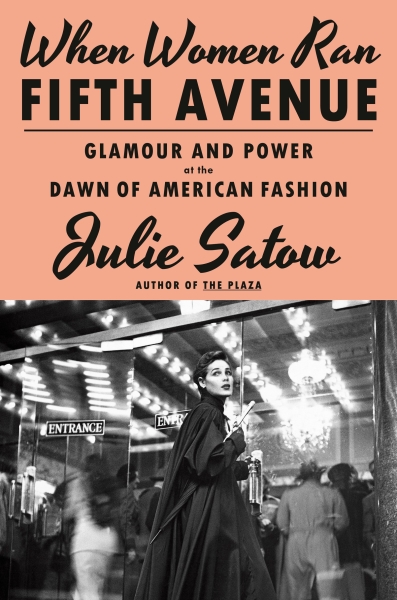

In Julie Satow’s latest book, When Women Ran Fifth Avenue: Glamour and Power at the Dawn of American Fashion, three women are spotlighted for their profound impact on the 20th-century fashion industry: Hortense Odlum (president of Bonwit Teller from 1934 to 1940), Dorothy Shaver (president of Lord & Taylor from 1945 to 1959), and Geraldine Stutz (president of Henri Bendel from 1957 to 1986).

“I had this concept that women in the workforce, in leadership roles particularly, was a more modern phenomenon,” says Satow, a journalist whose first book told the history of the vaunted Plaza Hotel. “It was fascinating, eye-opening, and rewarding to research this book and find out that there’s this whole generation of women that were breaking the mold before maybe a lot of us thought that was the case.” She adds, “Macy’s hired its first woman executive in the 1890s!”

In the early 20th century, the influence and role of the department store was akin to a fashion magazine’s: Without the internet or social media, if you wanted to know what was happening in fashion, you could either open an issue of Vogue or take a turn about a department store.

“Department stores were this kind of unheralded vehicle for fashion designers. Dorothy Shaver’s role was so critical to the creation of Claire McCardell and Elizabeth Hawes’s labels—Lord & Taylor, under her, was the first store to actually put the names of American fashion designers in ads,” Satow says. She adds that with Bendel’s, Stutz brought Sonia Rykiel and Jean Muir to the US and helped launch the career of Stephen Burrows. In other words, these women were fashion king-makers, disseminating and promoting clothing so that it journeyed from a designer’s atelier to retail mannequins to the bodies of Americans.

As the book’s title suggests, Odlum, Shaver, and Stutz were responsible for running their retail business on 5th Avenue, and Satow recounts their journeys to the top of the fashion industry. (As a bonus, she also sprinkles in shorter histories of another notable woman in fashion.)

Satow’s research required her to act as something of an archeologist, digging up as much information as she could to tell each woman’s story. She even went so far as to hire a genealogist to track down living relatives of Shaver and Odlum’s. “Dorothy [Shaver] had a grand-niece who happened to have a basement filled with all of these papers of Dorothy’s,” Satow reports, “so that was an amazing treasure trove.”

In honor of the book’s release date today, Satow shares with Vogue a few fun facts about these remarkable women.

Hortense Odlum, president of Bonwit Teller, 1934 to 1940

“Hortense had an autobiography that she’d written in the 1930s.

Her love rival was Jackie Cochran, who was a famous aviator [she was the first woman to break the sound barrier] and best friends with Amelia Earhart, which I think is a very interesting side story. She had a competition over her husband–her husband was a very interesting character, and he loved strong women, so he went from Hortense to Jackie Cochran.

She was Mormon and grew up in Utah and I went to the pioneer town where she grew up, which is St. George. It’s very beautiful, it’s right near Zion National Park. There, they have a museum called Daughters of Utah Pioneers which has amazing genealogical records. I was able to see all these records of her siblings and her family. She was the only one who had children, so I managed to track down her grandchildren who were still alive.

But she was a prickly character and was sort of estranged from her family—they didn’t have the warmest memories of her.”

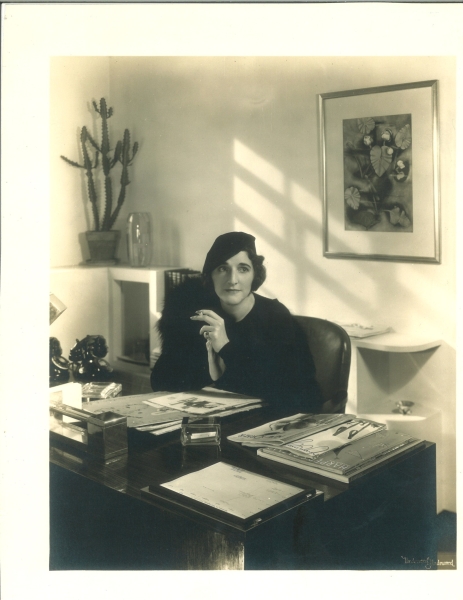

Dorothy Shaver, president of Lord & Taylor, 1945 to 1959

“She did not have any children and never married. Dorothy very much aped the male CEO. She was very much dedicated to being a very focused “businessman.” She was the first woman to earn over a million dollars a year—it was a published salary—and she was hugely influential in American fashion. She helped create the Costume Institute and was on the board of the Met Museum.

Dorothy’s role was so critical to the creation of Claire McCardell and Elizabeth Hawes’s labels—Lord & Taylor, under her, was the first store to actually put the names of American fashion designers in ads.

Lord & Taylor also had an entire department dedicated to American fashion designers—up until Dorothy, really, the concept that America could even have a fashion designer was anathema. It was only Paris.

Lord & Taylor under her had these annual awards, which were really big deals—a thousand people would come to the Waldorf-Astoria, and she had Albert Einstein and Twyla Tharp—these really important cultural, scientific, and intellectual people as honorees.

Life magazine had this article about her when she was appointed president around 1945, and they called her America's number one businesswoman. So she wasn't really considered a fashion figure, per se.

One thing that I found so cool was that she went to Stalinist Russia with her sister in the 1930s on an airplane when really nobody went on airplanes. She didn’t really care what anyone thought, you know; she kind of lived this eccentric life with her sister.”

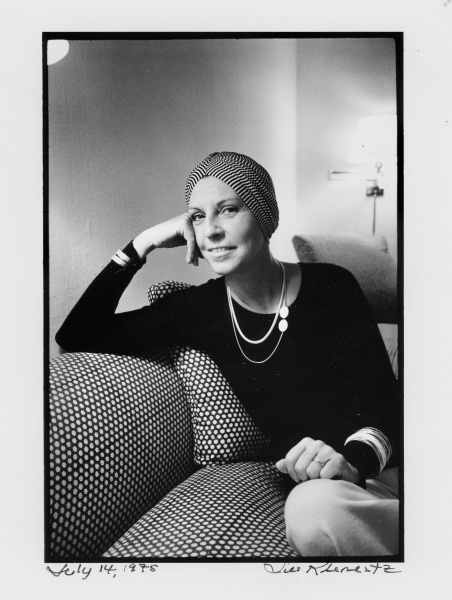

Geraldine Stutz, president of Henri Bendel, 1957 to 1986

“Geraldine is much more the modern female executive that we think of. Although she was married for a time, she did not have children.

Bendel’s was a much smaller store than the one Les Wexner moved it to on Fifth Avenue. It used to be on 57th Street, and it was this jewel box department store. It was much smaller than most other department stores, so it was really hard for her to compete with Bergdorf’s, for instance, or even Bloomingdale’s. Those stores would go to fashion shows and Paris and would place huge orders with designers and design houses like Chanel. Geraldine couldn’t compete with that because she didn’t have the floor space. So she had to be really creative in what she did in order to be successful.

Geraldine said to the main store buyer, ‘Go to Paris, go to Italy, go to all these places and go to the side streets. Don’t go to the big houses. Go look and see what people are doing in these little boutiques and find really cool clothing and bring it here.’ So she sent buyers into these stores. Sonia Rykiel, for instance, was just a little boutique; they saw these sweaters in the window, and her buyers went in there and saw they were amazing. They were the first ones to bring Sonia to America and to start selling her. They also did that with Jean Muir, and it was out of necessity,

At one point, the film director Joel Schumacher was doing windows for her, and he said, ‘Oh, you have to meet my friend, Stephen Burrows, he’s making all these amazing clothes for all these models and fashion people.’ And so Stephen Burrows came and showed her the clothes and she created a boutique for him and helped launch his career. She did that with so many people.

She also created these open calls. She used to be a magazine editor at Glamour, so she had this amazing fashion-editor kind of eye. Everything at Bendel’s was very curated, like in a magazine, but she needed fresh talent. So she created this open call and designers would line up around the block, and a lot of big designers got discovered this way. They would just show up with their wares and buyers would meet with them before the store opened and place orders. A lot of these designers went on to win Coty Awards right after showing at Bendels

There are amazing photos of her in the book and elsewhere. She really had the coolest style. She was really into turbans, and she wore lots of bangles down her wrist. They made loud noises because she often just gesticulated with her hands and arms. She was such an original.”